Establishing a Strong Northern Defense Against Nomadic Threats

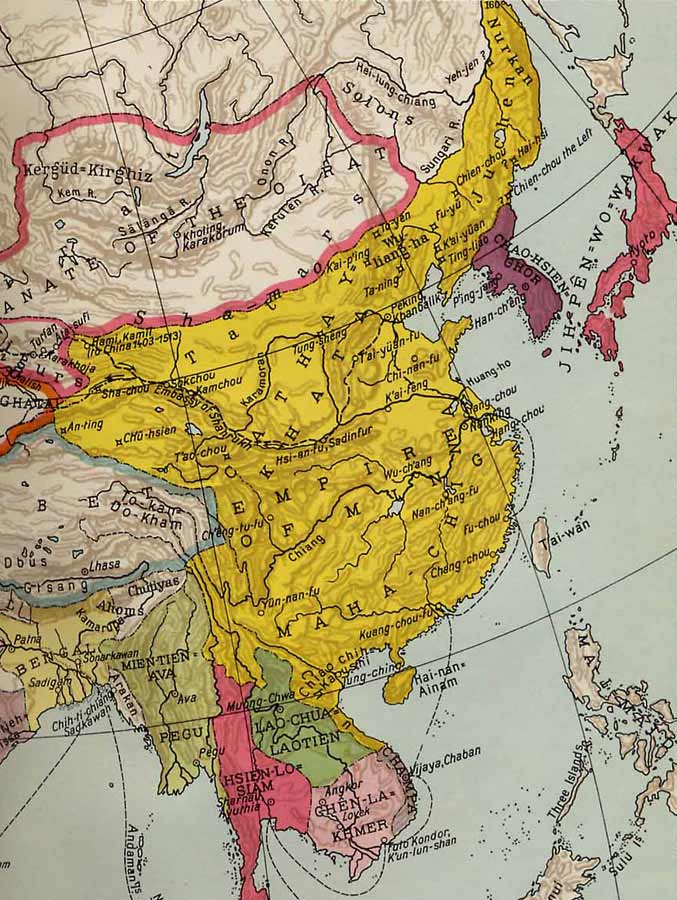

One of the primary reasons the Yongle Emperor moved the Ming capital from Nanjing to Beijing was to better defend against nomadic incursions from the north. For over a millennium, successive dynasties in China had faced repeated invasions from nomadic tribes originating from the vast grasslands and steppes north of the Great Wall. Empires rising in northern China, such as the Khitan Liao Dynasty and Jurchen Jin Dynasty, posed a similar territorial threat. The Ming had only recently overthrown the preceding Mongol-ruled Yuan Dynasty in 1368, establishing their regime further south in Nanjing. However, with the powerful Mongol military forces still occupying much of northern China and Inner Mongolia, the threat of a Mongol counterattack loomed large. Moving the capital to Beijing placed the Ming court adjacent to the northern frontier, better positioning it to respond rapidly to any nomadic incursions. The Yongle Emperor was also one of the most prolific builders of the Great Wall of China, constructing and upgrading defensive fortifications across the northern territories to deter the persistent nomadic menace.

Strengthening Control Over North China

Another strategic calculation behind relocating to Beijing was to consolidate Ming control and administration over the politically and culturally distinct regions of North China. For centuries, the northern plains had been subject to alternating rule by Chinese and non-Chinese regimes, holding a more tenuous relationship with Southern regimes based further south like the Ming. Establishing the capital at Beijing affirmed Ming sovereignty over the north and allowed for tighter governance and tax collection. It also neutralized the risk of semi-autonomous northern power centers emerging, as nomadic peoples and surviving elements of the former Yuan regime still held considerable influence. Consolidating administrative and military power in Beijing helped stamp the Ming imperial authority firmly over the northern heartland.

Leveraging Beijing’s Strategic Resources

Harnessing Northern Agricultural Potential

One strategic economic rationale for basing the Ming capital in northern China was to harness the productive potential of its vast agricultural hinterlands. The sparsely populated grasslands and steppe regions north of Beijing held underutilized potential for additional food production critical to feed growing urban and military populations. Under the Yongle Emperor, substantial tracts of land were appropriated to establish military farming colonies cultivated by conscripted peasant-soldiers. These frontier farms not only generated tax revenue and food supplies but helped maintain border security. Stationing the capital army corps in Beijing also reduced the imperial food and supply costs compared to maintaining them further south in Nanjing. Thus, northern development projects boosted agricultural self-sufficiency while consolidating frontier control and defense.

Leveraging Strategic Trade and Transport Routes

Another key factor was Beijing’s commanding position astride multiple strategic trade and transport corridors. As the junction point between Mongolian and Chinese cultures, Beijing served as a hub connecting Inner Asian trade routes with those running north-south through eastern China. Its central inland location along the Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal offered direct riverine access between North and South China. This crucial internal shipping route conveyed grain taxes, troops, and commercial shipments between the fertile Jiangnan region and northern territories. Situating the imperial court at this key logistical node provided oversight and taxation of the lucrative exchanges of people, goods, and taxes flowing along these vital economic arteries.

Establishing Dual Capitals in Nanjing and Beijing

While prioritizing northern defense needs, the Yongle Emperor did not fully abandon China’s traditional southern heartland. In keeping with long-established Chinese precedents, he instituted a compromise solution of dual capitals with secondary administrative functions also retained at Nanjing, the preexisting Ming capital city. Nanjing continued housing government offices and imperial palaces till the 1420s when construction finished on new Southern palaces in Beijing. This showed deference to traditional ceremonial rituals and the symbolic significance of Nanjing as the birthplace of the fledgling Ming regime. It also provided a safe alternate refuge in the event of a northern capital being overrun during an invasion. Thus, through a balanced dual capital system, the pragmatic Yongle Emperor successfully addressed both strategic security concerns and lingering Chinese political traditions.

Consolidating Power in Beijing, Yongle’s Political Base

However, crucial underlying the capital relocation was also the Yongle Emperor’s personal agenda to consolidate his control over the Ming imperial house. As the usurper Prince of Yan, Zhu Di had seized power from his nephew, the Jianwen Emperor, in 1402 in a bitter dynastic power struggle.

Many court officials and gentry families still remained loyal to the overthrown emperor in the southern heartland around Nanjing. By establishing his new imperial base firmly in northern Beijing, Zhu Di’s political power center, he removed this threat and influence from his southern rivals. The capital transition was thus enabled as much by power politics as strategic reasoning, strengthening the Yongle Emperor’s precarious grip on his nascent regime during its vulnerable early years.

In conclusion, a variety of pragmatic security, economic and political rationales contributed to the Yongle Emperor’s momentous decision to relocate the Ming imperial capital north to Beijing. While bolstering northern defenses against nomadic raiders, it opened agricultural and trading opportunities. Dual capitals also balanced strategic needs with longstanding symbolic traditions. Ultimately, the 1421 transition cemented the consolidation of imperial control by the usurper Zhu Di over his still divisive young dynasty.

An Insider's Guide to Enjoying Qingdao, China

An Insider's Guide to Enjoying Qingdao, China