Sanskrit is considered one of the oldest languages in existence with a rich linguistic history in South Asia. Often referred to as a classical language of Hinduism, it has had a profound influence across the Indian subcontinent. However, its origins and development over time are rather complex. This article aims to provide a comprehensive overview of Sanskrit by analyzing its various stages and relationship with other related languages such as Pali.

Origins and Development

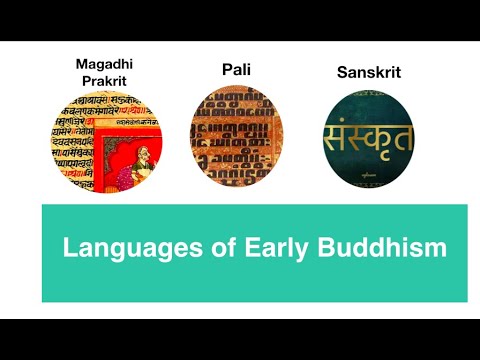

Sanskrit has its roots in the ancient Proto-Indo-European language dating as far back as 3500 BCE. Around 1500 BCE, it evolved into Old Indo-Aryan which was the primary language used in the Vedic texts. Regional dialects started emerging across India from 800-500 BCE called Middle Indo-Aryan languages. One such dialect was Pali predominately used in what is now Bihar and eastern India. However, scholars aimed to preserve the ritualistic language and grammar. This led to the emergence of Classical Sanskrit around 500 BCE under strict guidelines by grammarians like Panini.

Classical Sanskrit as a Standardized Language

Classical Sanskrit became the standardized literary language and a prestige dialect used by priests and nobility. While regional dialects continued to evolve, Classical Sanskrit was taught and propagated to maintain religious texts and ideals. It incorporated elements of older Indo-Aryan but followed a codified standard. No one spoke it as their native tongue by this period. Instead, it served as a lingua franca that united diverse populations through religious texts and high culture. This cemented its position for centuries as the primary medium of advanced education across South Asia.

Characteristics of Pali

Emerging from Middle Indo-Aryan dialects, Pali has considerable overlap with classical Sanskrit but differs in some key aspects. Phonetically, Pali absorbed characteristics from local Prakrits resulting in different consonant changes and vowel formations. Grammatically, it lacked complex Sanskrit rules involving nominal and verbal inflections. The PaliTipitaka scriptures also contain distinct vocabulary not found in Sanskrit. While heavily borrowing from older Indo-Aryan, Pali developed uniquely under the patronage of Theravada Buddhist monastic communities in central-eastern India.

Pali Literature and its Influence

The Pali canon contains some of the earliest surviving Buddhist scriptures compiled around the 1st century BCE. Containing discourses attributed to the Buddha, monastic rules, and philosophical treatises, it became the doctrinal basis for Theravada traditions in Southeast Asia. Monasteries played a key role in propagating Pali and established it as the prime medium of Buddhist scholarship across many Asian regions for over a millennium. Countries like Sri Lanka, Myanmar, Thailand preserved the legacy by using Pali along with local scripts for religious literature and rituals. Even today, it remains the official language of Theravada Buddhism alongside vernacular languages.

Comparison of Pali and Sanskrit Texts

A direct comparison of verses from the Pali Dhammapada and their Sanskrit versions illustrates the close yet distinct nature of both languages. While sharing a common syntactic structure and lexical roots, Pali diverges in phonetic rules and word formations. This reflects the natural dialectal drift as languages diffuse through geographical regions over time. Neither can certainly be called a direct ancestor of the other. Both enriched diversity within the broader Indo-Aryan spectrum through their roles in preserving early Buddhist and Hindu traditions respectively.

Mutual Influence Despite Differences

While Pali and Classical Sanskrit evolved as standardized registers, the linguistic landscape of India remained pluralistic. Regional dialects like Apabhraṃśa freely borrowed from both. Sanskrit literature incorporated vocabulary and styles from Prakrits to appeal to wider audiences. Similarly, Pali commentarial works demonstrate assimilation of Sanskrit technical terms. Their grammars also overlapped, attesting to continual exchange between the scholarly and monastic spheres. Differences were matters of degree, not substance. Both fulfilled crucial functions for preserving ancient knowledge systems in their respective religious communities.

Legacy and Significance Today

As natural languages spread and changed, Pali and Sanskrit persisted through active transmission by religious institutions. Despite losing native speakers long ago, they retain immense cultural capital and influence across the Indo-Pacific region. While Sanskrit survives prominently through Hindu rituals and philosophy, Pali remains in use for Theravada Buddhist doctrines in Sri Lanka, Thailand and Myanmar. Their continuity underscores the symbiotic relationship between languages and faith traditions. Studying Pali and Sanskrit sheds light on the dynamic intellectual life and diversity of pre-modern South Asia

Family Friendly Activities in Israel

Family Friendly Activities in Israel